Clock Divider

TL;DR

By default, PIO runs far too fast for most real-world interfaces. The clock divider lets us slow down how often a state machine executes instructions so the timing matches the device or protocol we are talking to. Each state machine has its own clock divider.

PIO state machines execute instructions at the system clock speed. On the Pico, the system clock runs at 125 MHz. This is far too fast for most real-world interfaces, so the state machine usually needs to be slowed down using the clock divider.

Each PIO state machine has its own clock divider. The divider slows down how often the state machine executes instructions, without changing the system clock itself. This means different state machines can run at different speeds, even if they are running the same PIO program.

The main purpose of the clock divider is to match timing requirements. Different devices and protocols need different speeds. For example, a UART might need 115200 baud, an I2C bus might run at 400 kHz, and an LED strip might need timing in microseconds. The clock divider lets you run each state machine at the exact speed needed for the protocol you are implementing.

Clock divider range and format

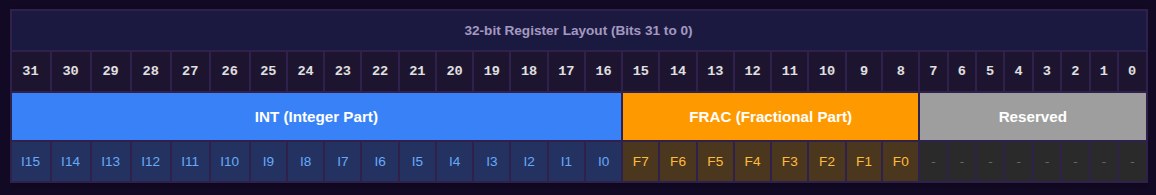

The clock divider is stored in a 32-bit register for each state machine (SM0_CLKDIV through SM3_CLKDIV). Each of these registers has a 16-bit integer field and an 8-bit fractional field; the remaining bits are unused. This means the divider can range from 1 to 65,536, and it can be adjusted in increments of 1/256.

Integer clock division

Instead of running one instruction on every system clock cycle, the state machine runs one instruction every n system clock cycles.

If the clock divider is set to an integer value n, the effective state machine clock is:

f_sm = f_sys / n

For a 125 MHz system clock:

- Divider set to 1 results in a state machine clock of 125 MHz.

- Divider set to 125 results in a state machine clock of 1 MHz.

- Divider set to 12,500 results in a state machine clock of 10 kHz.

Fractional clock division

The clock divider is not limited to whole numbers. It also supports fractional division, which allows finer control over timing.

The divider value is:

n + f / 256

where:

- n is the integer part

- f is the fractional part, from 0 to 255

For example:

Divider = 10 + 128/256 = 10.5

The effective state machine clock then becomes:

f_sm = 125 MHz / 10.5 ≈ 11.9 MHz

In Rust

In Embassy, this value is represented using a fixed-point type, FixedU32<U8>. We have already seen something similar in the PWM section, where fixed-point values are used in a comparable way. You can also refer to the linked blog post, where fixed-point representation and the fixed crate in Rust are explained in detail.

FixedU32<U8> means it is a 32-bit value where the lower 8 bits represent the fractional part and the remaining upper bits represent the integer part. Well, did you get the same confusion as me? If you look at the PIO clock divider register layout, the fractional part actually starts at bit 8, and the integer part occupies only the upper 16 bits. But If we store the value directly like this, it will be incorrect, because FixedU32<U8> conceptually has 24 integer bits and does not match the hardware layout.

To clear this doubt, I followed the code path that writes into the clock divider register. It turns out the value is shifted left by 8 bits before being written.

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

sm.clkdiv().write(|w| w.0 = config.clock_divider.to_bits() << 8);

}After this shift, the fixed-point value lines up with the hardware register layout exactly.

It is not easy to represent the PIO clock divider fixed-point format directly using the standard fixed crate, because the hardware layout does not map cleanly to it. So that is why Embassy seems to have chosen this approach, at least that is what I think.

How Clock Divider Affects Instruction Timing

When we run PIO at the system clock speed of 125 MHz without any clock divider, the state machine executes one instruction every 8 ns. We have seen a similar calculation earlier when we discussed PWM frequency and period.

A clock speed of 125 MHz means there are 125 million clock cycles per second. To find how long one clock cycle takes, we divide:

\[ \text{clock cycle time} = \frac{1}{125{,}000{,}000} \text{ seconds} = 0.000000008 \text{ s} = 8 \text{ ns} \]

This means one system clock tick takes 8 ns. When the clock divider is set to 1, one PIO instruction is executed on every clock tick.

In general, the relationship looks like this:

\[ \text{instruction time} = \text{clock divider} \times 8 \text{ ns} \]

The clock divider directly controls how many 8 ns system clock ticks make up a single PIO instruction. By choosing the divider carefully, we can make PIO instructions run at time scales that are easy to work with, such as microseconds or milliseconds.

Example

Let us say we set the clock divider to 125. This tells the state machine to wait for 125 system clock ticks before executing the next instruction. Since each clock tick takes 8 ns, the time taken for one instruction becomes:

\[ \text{instruction time} = 125 \times 8 \text{ ns} = 1000 \text{ ns} = 1 \text{ µs} \]

So with a clock divider of 125, one PIO instruction takes 1 microsecond. This means the state machine executes 1 million instructions per second.

If we want the frequency instead of the time, the calculation is straightforward, just like in the PWM case:

\[ \text{state machine frequency} = \frac{125\text{ MHz}}{125} = 1\text{ MHz} \]

So the effective state machine frequency is 1 MHz.